The automation of the textile industry has meant that production, especially in developing countries can be monetarily economical, yet environmentally expensive.

This report aims to identify key areas within the textile, fashion, backpack, luggage and clothing industry that with change and development would resolve some, if not all of the immediate ecological issues. This report will focus on the current and future problems within the textile industry.

Introduction

“A minimum of 50% of all waste deposited at Household Waste Sites will be recycled/composted by 2005/6 and 55% by 2010/11”

Managing waste for a brighter future, The Joint Municipal Waste Management Strategy for Herefordshire & Worcestershire 2004-2005.

The current market for textiles worldwide is greater than ever before, with a current worldwide demand for textile fibres growing some ‘5.4 percent annually through 2005, driven by solid gains in synthetic fibres such as polyester and olefins. Manufactured fibres will expand their market share over natural fibres. The global fibre industry will continue to shift to the Asia/Pacific region, particularly China, South Korea and Taiwan.’[1]

Already the third largest consumer of natural resources, this level of increased textile (specifically synthetic fibre) production is showing effects in those geographical locations where production is high and increasing. Both in the depletion of natural resources, reliance on cash crops, increased pesticide, fertilizer use, child enforced labour (other unethical working practices), localised and nationalised air, sea and land pollution and all of the associated direct health implications.

Through this report, an analysis and a justification can be made for the development of a less wasteful, ecologically ‘sounder’ solution to the mounting problems textile production is contributing to a host of environmental issues. This report will look at the trends that are causing the greatly increased production of textiles, what happens to these textiles once they are disposed of, and how this must be addressed globally.

By looking at what the UK Government is hoping to achieve with its recycling manifesto and how this directly relates to textiles, we can test the viability of non-virgin[2] materials being used to reduce the amount of:

- New or ‘virgin’ textiles put into production.

- Textiles going into landfill.

And increase the:

- Efficiency of recycled textiles.

- Quality of recycled textiles.

“What do we do with all this recycled material?”

Whilst capturing the ever more ‘eco-aware’ public’s attention; it is hoped that this report can be a realistic solution to be adopted world wide, to help slow down the damage being done to the earth.

UK Recycling – Textile Recycling

Recycling Trends

Until the later half of the 20th century, there was no concept of what we refer to today as recycling. Prior to and including the war years people were of a financial situation where by ‘make do and mend’ was not only encouraged as ‘war effort’ but was adopted because of economic reasoning.

“Clothes rationing was introduced in 1941. Adults were rationed to a fixed number of clothing coupons per year, each item of clothing having a coupon value, plus the price fixed by law. If you had the money, but no coupons, you could not buy, although an illegal black-market grew up of traders willing to supply the unobtainable, but at a price. Thus a ‘make-do and mend’ ethos grew up, recycling old clothes, unpicking the wool from old pullovers to darn socks, for example.”[3]

Items of clothing, household appliances, tools and machinery were all constructed in such a manner that allowed for home repair, and therefore had a considerably longer ‘life’.

Today no such situation exists, home or professional repair of household goods is a logistical nightmare. The repair of all but the most expensive clothes is unfeasible. Manufacturers are aware of this so that consumers are forced to replace, not by choice, expensive (ecologically) everyday items on a regular basis. Planned obsolescence of products, from mobile phones to cars is part of the design process of all major companies.

EU regulation is being brought to counter this situation.

“The EU Directives on Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) and the Restriction of the Use of certain Hazardous Substances (RoHS) were published in the Official Journal of the European Union on 13 February 2003 and must be implemented into UK law by 13 August 2004.”4

This directive puts in place controls over who is responsible for the aftermarket processing of electronic goods. And states how these items must be processed.

“In terms of electronic appliances, recycling will include the recycling of metal components into new metals, reprocessing plastics into recycled plastics, etc. Recovery includes these recycling operations but also includes activities like incinerating plastic waste with energy recovery.”[4]

Furthermore the costs associated with the onward supply and management of WEEE will be met by the producers of the equipment. This is a logical step and should further encompass the textiles industry, however it does not address the problem of over consumerism, nor does it address the problems caused directly at manufacture. See Chapter Four. Indeed, it could be misconstrued that it may make manufacturing even more competitive, with regulations being skipped; Cynical though it may seem the end consumer is likely to foot the bill, and little or no change will occur.

What, Why and Where?

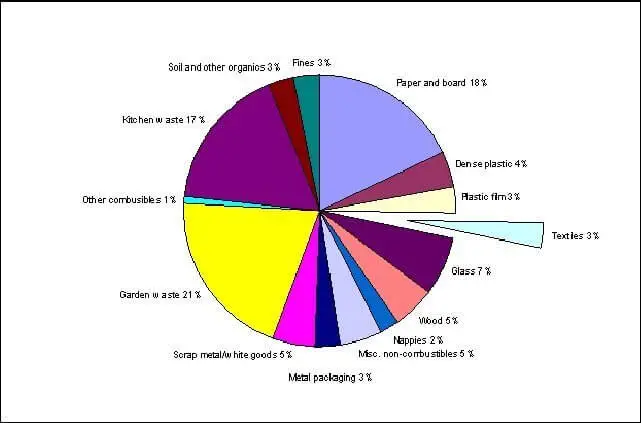

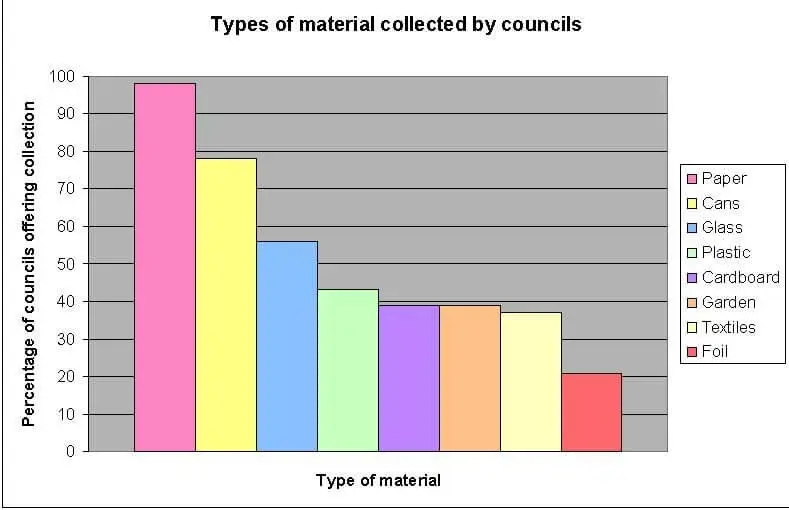

Items that have entered into everyday UK recycling habits include: paper, glass, aluminium (and other metals), some plastics and textiles. Indeed, it is these household waste items that have been targeted and encompass the Government’s Waste Management Strategy.

Up to 80 percent of household waste is theoretically recyclable, and rates of 50-60 percent recycling are already being achieved in some UK districts6. The 20 percent of products which aren’t currently recyclable (some plastics, sanitary products, household batteries etc) should, with time be redesigned to allow them to be recycled.

The success of these items returning to a third or fourth use is arguable, with many recycling processes inefficient or the properties of the material degrading to such an extent that it is unviable to reprocess any further.

Recycling makes sense, if it’s being consumed and it’s being produced, there is going to be a demand, and until consumers alter their perceptions and requirements, and there is no waste, recycling will exist.

Currently there are initiatives and Government incentives to local districts to start collection services for separated waste collection at door stop. In reality there are to be financial penalties if the European targets of 30 percent of household waste in 2005 is not recycled, increasing to 33 percent in 2010.

Recycling should be made efficient easy and an everyday occurrence, and therefore should be everywhere, in reality enforced door stop collections are the most effective.

-

What will this achieve?

Recycling is an industry in its own right, after processing the recyclable products a new product can be produced. In the most modern of processes, the secondary product can be indiscernible from the original. Recycling is a direct way of protecting our natural resources, it helps reduce the amount of material going into landfill, and it is an efficient way of dealing with increasing levels of waste.

By recycling consumers also become educated as to what they are using, and indeed wasting. Although there have been studies showing that recycling promotes a more carefree attitude with regards to excessive packaging and general consumption; traditional consumer trends have not fluctuated to such an extent that this is anything more than a localised anomaly.

Problems and misconceptions

Specific problems include but are not limited to:

- Poor second or third product use etc.

- Severe degradation of quality.

- Inefficiency can be severely environmentally damaging

- Public over confidence, and excessive over use

- Being used just as a marketing tool

There is often the misconception that all recycling is good, many forms of material especially textiles are effectively only ever recycled once. Many forms of plastic recycling is performed to such low standards as competition in this market is so fierce that the secondary material will never be of sufficient quality to be recycled. It can also be stated that the most common form of household recycling and recycled product use, newspapers benefit greatly from the abundance of paper pulp, and therefore don’t work effectively managing their paper usage.

Recycling data

The rates and success of recycling across the UK is varied, with some districts still to introduce door stop collections. Data relating specifically to the analysis of textile recycling habits and attitudes is often poorly included within data as co-mingled. See chapter one – subsection ‘Textile recycling’.

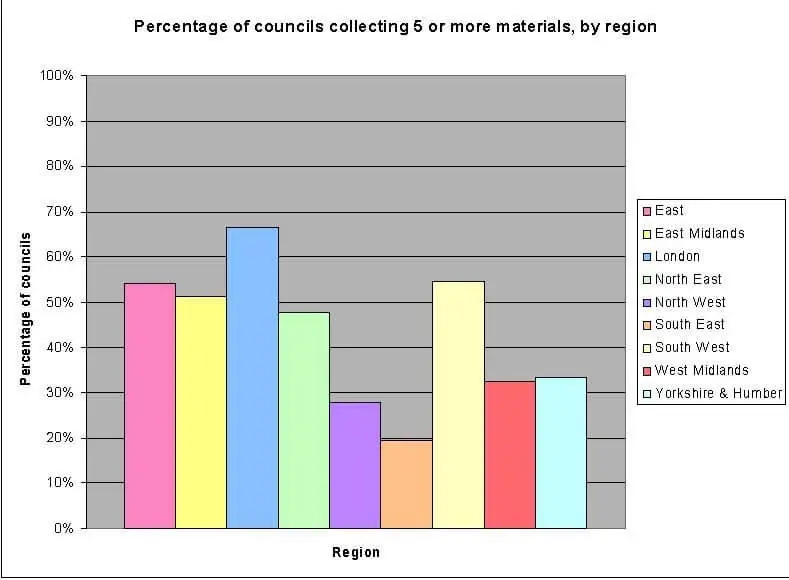

Summarised data from Friends of The Earth research report ‘Door Stop Recycling in England’ shows how each of the districts are performing and what services they are providing:

Ten of the best doorstep collections in England[5]

1.Daventry District Council

The council runs a sophisticated collection for 100% of its households: a weekly separated collection of dry recyclables alongside a fortnightly alternating refuse / compost collection. The scheme has catapulted

Daventry to the top of the UK recycling league table.

2.Salford Metropolitan

The council provides a collection of 6 materials to 100% of its households and separates the recycling onBorough Council street. Households have to opt-in and the participation rate is around 44%.

3.Lichfield District Council

Lichfield is the only authority in the West Midlands region which offers a collection of more than 5 materials to 100% of households. In fact, 7 materials are collected separately every week. The collection is separated on-street and run in-house. There is an 8090% participation rate.

4.London Barnet

The council uses ECT recycling (a not for profit Borough of company) to offer a 6 material weekly collection to 100% of its households. The collection is separated onstreet. The participation rate is around 50%.

5.Wear Valley District Council

A council-operated collection of 5 materials is offered to 100% of households on a fortnightly basis, separated on-street.

6.Darlington Borough Council

The collection of 5 materials once a fortnight is offered to 100% of its households, with an estimated participation rate of 50-60%. The in-house operated collection is separated on-street.

7.St Helens

The council offers a collection of 6 materials every Metropolitan fortnightly to 100% of households. The scheme is Borough Council separated on-street and run by Cheshire Recycling.

8. Vale of White Horse District Council

A 6 material collection is offered every week to 100% of households and the participation rate is estimated at Council 74%. The materials are separated on-street and the scheme is operated by ECT recycling (a not for profit company).

9.West Oxfordshire District Council

ECT recycling offers a fortnightly 5 material collection to 100% of households. The separated scheme will expand to collect plastic bottles, aerosols, cardboard and batteries from April 04.

10.North Cornwall District Council

A 7 material separated collection is offered to 100% of households fortnightly, operated by Cornwall Paper Council Company. The participation rate is 55%.

The worst doorstep waste collections in England

Bromsgrove District Council No doorstep collection is offered. The council is planning to introduce one between March 04 and January 05.

East Riding of Yorkshire No doorstep collection is offered. There is a proposal to introduce a paper collection but the start date was not provided.

Warrington Borough Council Only 6% of households in Warrington get any kind of doorstep collection, and that just picks up paper – once a month. The scheme is run in-house.

Sheffield City Council In April 2003, waste company Onyx introduced a doorstep collection of paper and cardboard which picks up just once a month. Households put out their mixed paper, magazines and cardboard in large (140 litre) wheelie bins. Sheffield’s recycling rate was just 4 per cent in 2002-3 one of the lowest in the country. Its doorstep scheme reached just 9 per cent of households in 2002-3. Although Sheffield Council has reported to us that they are now reaching 85 per cent of properties with their scheme, they still have a long way to go.

South Lakeland SITA collects just one material, paper, from half the households in South Lakeland. The other half of households receives no collection.

Kettering Borough Council Although Kettering offers a 4 material collection to some of its households, the vast majority – 89% – do not get any service at all.

City of London The waste management company Bywaters collects paper and card mixed together from just 37% of City of London households.

Middlesbrough Borough Council Only paper is collected in Middlesbrough (by Cheshire Recycling). The council acknowledges that it will need to catch up with other authorities by collecting more types of materials within the next year or so.

Liverpool City Council Liverpool offers a collection of just 1 material, paper, and 15% of its households don’t even get that.

Friends of the Earth ‘Doorstep Recycling in England’

Friends of the Earth ‘Doorstep Recycling in England’

Also of note is the spread of waste across England, with specific high concentrations of waste producing districts in the West Midlands and South West, and how this relates to the relevant areas performance of doorstep collections. There is negative correlation, with Greater London producing the least waste, yet offering the highest percentage of councils collecting the maximum number of recyclable materials.

Textile Recycling – textile recycling in the fashion industry

Textile recycling falls into the category that is least well documented and the data often confused, a variety of items may or may not be counted as textiles, and the data, as seen here varies wildly.

It is estimated that 400,000 to 700,000 tonnes of textiles are land filled every year, worth an estimated £400 million. At least 50% of the textiles going to landfill are recyclable. The amount of textile waste reused or recycled annually in the UK is estimated to be 250,000 tonnes.[6]

Severn Waste Management, the contract operators for waste management within the Hereford and Worcestershire districts retained no corroborative data to support their claim that 400 tonnes of textiles from its collection points in the Pershore area was actually recycled.

There were no statistics available either from any of the major charities regarding the percentage of its clothing, unsuitable ‘for sale’, getting recycled, or specifically its exact destination.

Potential destinations for recycled textiles:

- Abroad – to be worn typically in developing nations

- Home – to be reused, as is resold or handed down

- Reprocessing – fibre content broken down to be reused – Khadi Board – Backpack Canvas

- Rags – to be used in various industries

Households donating unsuitable items for resale in this country might simply be offsetting the problem of locked in chemical land fill to another country.

Or delaying the time for that garment to become unusable in this country then be irresponsible disposed of; turned to rags which, once used are unsuitable for reprocessing, contaminated and incinerated or land filled.

Case Study:

- Of the garments not sold in the shops, 70 per cent are sold overseas. Good quality, second-hand clothing is packed for export sale to more than 18 countries.

- The majority goes to Africa, where there is huge demand for quality, affordable, second-hand clothing.

- Another 25 per cent of items collected are recycled for the fibre content, or for use as mattress filling or as industrial wiper cloths.

- Only five per cent ends up as unusable ‘waste’.9

Reprocessing of Recycled / Reclaimed fabric – making Khadi

The nature of textile design means that in any taken sample of donated or collected textiles a vast range of fibre types will be found.

As a recycling solution this presents a problem, immediately meaning that sorting needs to be extensive, usually involving a human and manual element. The nature of clothing and fashion also predisposes the articles to be embellished with a variety of items.

- Closing devices – zippers, poppers, studs, hooks, Velcro

- Interlinings – padding and structural stiffeners

- Linings – fillings – Khadi Backpack Lining

- Labels

- Embroidery

Once the articles have been sorted they must have all embellishments removed, they can then be broken into fibres of varying qualities[7].

Where does it go?

This ‘raw’ material is used in a variety of situations, some applications of which are somewhat secretive, dependant on the level of sorting at process these include:

- To ‘bulk up’ Virgin materials in the production of yarns – Khadi Hand spinning in Kolkata India – e.g. Canvas for backpacks

- Khadi Board – canvas and cloth for backpacks

- For the production of Felt – straps and padding

- Carpet backing yarn

- For car muffling felts

- For mattress and other stuffing applications

How much is produced?

It has not been possible to ascertain the exact production levels of this shoddy. The remaining processing plant in the UK handles over 1000 tonnes of shoddy per year11. The total UK production levels are maintained by this one company, Cullingworth Summers & Co, who recently suffered from a fire destroying half the plant.

This area is in general decline; historically the shoddy trade dealt with faulty material from the mills, and as such could maintain a higher level of quality. With the methods employed by the mills, this is a much rarer occurrence, and the majority of what becomes shod is obtained through charity and council collections.

How can the resultant recycled fibres be improved?

By introducing a logical, systematic collection of textiles, and by public awareness exercises the processing and sorting of garments could be speeded up. An industry body should be held responsible, and textile manufacturers should be encouraged to participate. Garment adornment should be analysed for compatibility with this process. Adding value to any reclaimed fibres is important – making products that have a long and lasting life cycle – such as tough and well made backpacks is just one solution.

What is the UK Government doing?

There are currently no plans to expand or extend recycling to cover the processing of textiles in an ecological manner. Investment for recycling and recycling initiatives is being reduced; the Waste & Resources Action Programme[8] the UK organisation for the development of initiatives in recycling will not fund initiatives regarding to textiles, and is operating on a gradually reducing budget.13

What People Think About Recycling

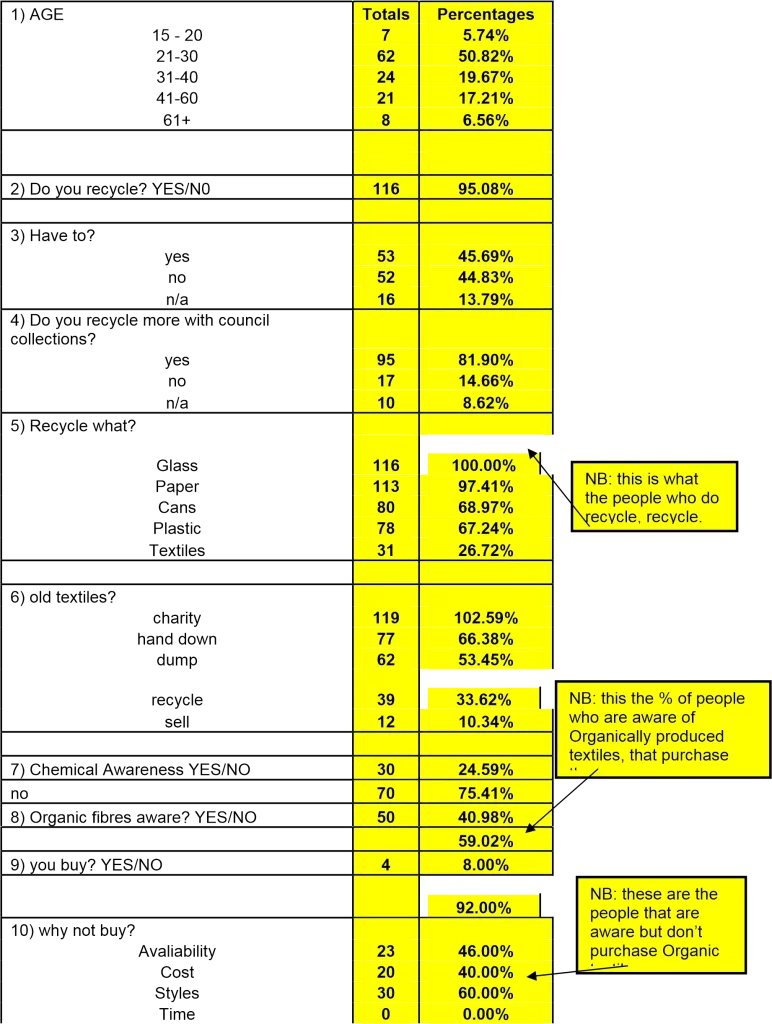

This small scale survey reflects the results of both the WasteOnline research and the of ‘The Friends of the Earth’, ‘Doorstep Survey’.

Slight localised differences are apparent, Glass and paper in recycled quantities are swapped, this may be due to the way that the three surveys differ, and the way Council depots calculate collected items by weight, rather than volume.

- A large proportion of the survey recycled because they wanted to not because they were enforced to do so.

- 3.28 percent of the survey (those living in Hereford/shire) were enforced to sort and recycle, with £1000 fines enforceable.

- Doorstep collection increased recycling

- Everyone donated to charity shops, even those who were non recyclers (4.92 percent)

- A large contingent handed-down textiles (garments) within family and friend environment

- 53 percent discard their textile for land fill

- Only one quarter (25.4 percent) of those surveyed had knowledge of use of chemicals in textile manufacture and garment construction.

- There was a general awareness of the existence of Organic clothing

- 8 percent of those aware, bought organically produced textiles

- Those that did not buy blamed availability, and styling as reason for not purchasing, 27 percent blamed cost.

- 92 percent of those surveyed (111 people), were not aware of the destination of garments or textiles that were handed to charity or deposited in council collection bins.

Ecological Issues in Textile manufacture – Ethical Fashion Trade

“More than 8,000 chemicals have been identified by the German textile industry to be in regular use for production and processing of textiles. Of these nearly 200 are hazardous, though some cannot be tested at all or the tests are too expensive. While the impact of these chemicals has not been sufficiently investigated, the textile industry in developed countries, starting with Germany, has voluntarily started advocating ecolabels on textile products to enable consumers to buy “clean” products.”[9]

Fierce competition and accelerated markets have forced producers of many natural fibres to take drastic and often dangerous action. Crop failure is not a situation that can be tolerated, or absorbed; excessive use of chemicals even with their intrinsic problems is common.

Since the first of January 2005, removal of all worldwide textile and clothing quotas has seen a boom in exports from developing nations.

“Exports to the United States of cotton-knit tops, one of the items affected by quotas, surged to 11 million units in the first five months of this year, compared with 2.8 million units during all of last year.”16

Especially key to this is the large increase of low end consumables, where profit margins are very narrow.

The range of chemicals used in the processing of textiles is wide ranging, the key areas of use are for the growth/development of:

- crops

- livestock

Processing:

- tanning

- treating

- stabilising

Post process:

- dyeing

- embellishment

- finishing

What chemicals are used?

A host of different Chemicals are used as already stated, but these can be broken down into function.

Pesticides and Herbicides:

In excess of 20 separate groups of pesticides are recognised as posing both a health risk at the consumer end, and at the cultivation of natural plant fibres such as cotton and flax. For Example:

Aldrine, carbaryl, DDD, DDE, dieldrine, endosulfan, endrine, heptachlor, heptachlorobenzene, lindane, methoxychlor, trifluralin.[10]

Pesticides are used to prevent attacks and crop failure by insect attacks, whilst herbicides are weed-eradication and defoliant chemicals.

These particular pesticide and herbicides are rated from slight to highly toxic; various attributable effects on the soil are recorded.

Lindane is a pesticide and assumed to be carcinogenic.[11]

Textile Finishes

Pentachlorophenol (PCP) and 2,3,4,5,6 Tetrachlorophenol (TeCP) are both used to prevent mould caused by fungi, both applied directly to textiles are considered to be highly toxic.

Both have high chemical stability, remaining difficult to break down, posing a long term threat to people and the environment.

Organotin Compounds – TBT and DBT, Tributyltin is a anti microbial finsh used to prevent sweating odours. Dibutyltin is another organotin used variously as a stabiliser, and in the manufacture of polyurethanes.

High concentrations of these compounds are considered toxic; absorbed through the skin they can pose damage to the nervous system.

Formaldehyde is used for creation of easy care finishes, preventing shrinkage, helping crease resistance and gives a soil releasing finish.

Textile Dyes

The breadth of dyes is massive.

Azo dyes (nitrogen based) are heavily restricted in the EU under the Azocolourants Directive 2002/61/EC[12]; they have been proven to separate under certain conditions to produce carcinogenic and allergenic aromatic amines.

Chlorinated Organic Carriers commonly used in the process of dyeing polyester, they have been found to cause liver malfunction, irritation to mucous membranes, skin and reproductive problems.

Heavy metals are constituents of some dyes, but they may also be present in a fabric having been absorbed by plants from polluted soil.

They pose extremely serious effects when absorbed into the body.

Typical heavy metals include:

Antimony, Arsenic, Lead, Cadmium, Mercury, Copper, Chromium, Cobolt and Nickle.

It is important to note that regulation within the EU is strict. These chemicals are still commonly used in developing countries, and it is the workers in direct and indirect contact with these substances that are affected. It is also to be noted that as stated before it is the lower end of the price market that has seen the significant jump in exportation from developing nations, these are intrinsically linked to poor chemical/environmental and human protection and control

Direct Environmental and Ecological effects of the Fashion Industry

Excess or even prolonged use of pesticides and herbicides on the environment can have pronounced effects.

Prior to its ban DDT[13] and PCB[14], of which PCP is a derivative is blamed for the poor formation of bone structures in vertebrates; 12,000 birds washed up on UK shores (1969) were found with higher than expected levels of PCB.[15]

High levels of PCB’s in animals can cause infertility, at 50ppm in Whale Blubber there is a sharp cut off in levels of fertility:

- In 1991 the Ministry of Agriculture found a dead bottlenose dolphin with PCB levels of 320ppm of the coast of Wales.

- Killer whales have been found with 410ppm of PCB

- Dolphins off the coast of Europe – found with up to 833ppm PCB[16]

All considerable distances from PCB pollution.

Fertilisers

Excess release of fertilisers, essentially Nitrates and Phosphates in large quantities – used extensively in the cultivation of cotton and flax, into the water table can lead to eutrophication.

These provide nutrients for algae’s, which can grow at such a rate that light essential for other plant life is cut off; with such swift over production of algae free oxygen levels are left depleted, and all marine life can die.

Follow on repercussions are that whole water systems can be infected, and disease will quickly follow. Globally, up to 30 percent of all fertilisers used are for the production of textile fibres.

Soil degradation

Any excessive cultivation will change the natural characteristics of soil, and environment. Deforestation for cattle ranching is a typical example where desertification occurs, taking many years to return.

Chemical contamination can persist for years, altering not only habitat, but also environment patterns such as rain fall.

Global Climate Change

Many of production methods in the developing nations are in-economic with regards to natural resource usage, contributing further to the release of atmospheric pollutants, namely Carbon Dioxide, Nitrous oxide and CFC’s amongst others.

C02 CH4 and N20 increases

Transport of Fashion Goods

As more production is put into developing nations, with markets further away reliance on global travel is a necessity.

With a continued reliance on air flight, a significant rise in the Earth temperature has been attributed directly to this phenomenon.

Air flight effects on climate

Ethical Fashion Trading

It must be noted that in developing nations working conditions in every aspect can be very poor. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) has estimated that there are about 250 million child workers in developing nations between the ages of 5 and 14, 120 million working full time.[17]

The World Health Organisation (WHO) states that in developing nations:

- Pesticide formulators, mixers, applicators, pickers, with single, short-term and very high level exposure will suffer 3 million persons exposed annually, with 220,000 deaths (annually).

- Pesticide manufacturers, formulators, mixers, applicators and pickers, with Long-term exposure there will be 735,000 people suffering from specific chronic effects of long term exposure (annually).

- All population groups with long-term low level exposure will suffer 37,000 chronic effects of long term exposure, Cancer (annually)

Eco-fashion Market

“For decades, the terms ‘Eco’ and ‘Luxury’ seldom intertwined in the fashion world. All too often, the environmentally aware were confined to wearing shapeless sacks of ill-woven fibres to be true to sustainable style.

Fashion thrives on marketing, and quirks sell. Does that mean with the creation of potentially ecologically sound garments and backpacks, or rather the touting of such garments that there is going to be a revolution of the textile markets? Investigating various claims afforded by designers we find that for some, the term eco-friendly is only very loosely employed. There appear to be distinct routes for something to be claimed as eco friendly, and various levels of compliance with what is recognisable as a truly ecologically sound solution, in what is essentially a self regulated industry.

- Bio Degradable

- Recycled – Recycling by definition means reusing something, how many times this can be done determines how efficient that recycling process is.

- Organics – There are a variety of levels of organic materials available for the production of yarn. Organic cotton, linen and hemp are all examples.

- Wools – Consideration must be given to the wool mills that for centuries have reclaimed fibres and mixed them with higher grade virgin fabrics. It is an unfortunate situation that this has never been developed further; most probably due to the decline in the UK textile industry, but also because of the appeal of the New Wool mark. The New Wool mark will maintain a high retail status; and with the unstable market it is perhaps understandable that new initiatives have been looked at wearily.

- Hand recycled non virgin fibres made into a huge range of fabrics utilised in the Indian textile Industry and perfect for Khadi backpacks that last.

- New Developments – Consideration must be given to a host of new textiles that have been developed since the late 1990’s. A Viscose alternative developed by Ingeo, from processed corn starch is a viable textile. Produced essentially from waste, the resources required to manufacture the material are high; and practical application for the fabric, which cannot be readily heated without melting, nor woven to greater gauge than that used for underwear or swim wear, is minimal. The raw material is also non organic, and if developed in it own right there is the potential for corn to be produced solely for its manufacture. There are similar developments with lactose from cows milk, sharing the same problems as the Ingeo fabric.

Until a very short time ago the UK public were only able to recycle a few materials, all of their own volition. Today we have a large percentage of district councils implementing doorstep collections for recyclable materials. With feasibility studies stating that up to 80 percent of household waste can be recycled, what are we to do with this uncapped resource? Much of what is collected already has major industries, paper, glass, metals and plastics all have in place infrastructures to deal efficiently with their reclamation and reprocessing. Textiles, the forgotten one however, has not. It has been shown that there is not strict regulation for the collection of any textiles. No dynamic or indeed creative ventures for this resource.

So where does one go next?

Through design initiatives, and extensive research and development many products that would once have been grown or mined for the purpose of covering our backs can come from our bins. We can help reduce the massive scale of environmental damage caused simply by the over production of cotton, if we are able to implement real world solutions and embrace textile recycling just as we have glass.

Bibliography

P.C. Sinha, (2004) Encyclopaedia of Ecology, Environment and Pollution

Sara Hulse, (2000) Plastics Product Recycling: Technology and Market Trends.

A. Richard Horrocks, (1996) Recycling Textile and Plastic Waste.

Brenda Platt, (1997) Weaving Textile Reuse into Waste Reduction.

Olga Nieuwenhuys, (1993) Children’s Lifeworlds: Gender, Welfare and Labour in the Developing World.

Ambika Prasad Diwan, (2002) Recent Advances in Environmental Ecology.

H.-K. Rouette, (2001) Encyclopedia of Textile Finishing.

Jeremy Seabrook, (2001) Children of Other Worlds: Exploitation in the Global Market.

Kevin T. Pickering & Lewis A. Owen, (1997) Global Environmental Issues 2nd Edition.

Craig Donnellan, (2002) Child labour Issues, Volume 46

Joseph Stiglitz, (2002) Globilazation and its discontents

Paul Roberts & Lucy Glynn, (no date) Friends of the Earth, Recycling in action, leading case studies across England and Wales

Joints Members Waste Forum – Hereford & Worcestershire, (2001)

Managing Waste for a Brighter Future

Jeffery Wilson, (2005) Ecological Foot Prints of Canadian Municipalities & Regions

www.clothesmadefromscrap.com/pet.htm

www.textile-recycling.org.uk/recyclatex.htm

www.biothinking.com/studentfaq.htm

www.recyclinginternational.com

Interviews

Paul Allen, Pennine Fibres, telephone interview

Roger Polsen, Colsen Weavers, telephone interview

Paul Cullingworth, Fibre Reclaimers, Cullingworth Summers & Co, telephone interview

David Elks, Intertek Laboratories, telephone interview

David Keenan, Keenan Glass Studio, visit and correspondence

David Austin, Abimelech Hainsworth, telephone interview and correspondence

- Source – http://www.freedoniagroup.com/World-Textile-Fibers.html ↑

- Non-virgin a colloquial term used in this report to identify materials previously used, i.e. recycled. ↑

- Source – www.bbc.co.uk/history ↑

- Source – www.dti.gov.uk 6 Friends of The Earth (interview) ↑

- Friends of the Earth. PDF – ‘Doorstep Recycling in England’ March 2004 ↑

- Analysis of household waste composition and factors driving waste increases – Dr. J. Parfitt, WRAP, Dec 2002 9Source – www.Oxfam.org.uk – WasteSaver ↑

- Often referred to as ‘shoddy’ 11 Source – Paul Cullingworth director of Cullingworth Summers & Co ↑

- www.WRAP.org.uk 13 Source – Wrap representative ↑

- Source – Cuts-International – Textiles and Clothing – Who Gains, Who Loses, and Why? May 1997 16 Source – China Daily – May 2005 ↑

- Source – Intertek textile testing lab ↑

- Source – Intertek textile testing lab ↑

- Source – Intertek textile testing lab ↑

- Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloro-ethane ↑

- Polychlorinated biphenyls ↑

- ndSource – an introduction to Global Environmental Issues 2 edition. ↑

- ndFigures – an introduction to Global Environmental Issue 2 edition. ↑

- Child Labour Issues volume 46 ↑

- Source www.luxuryeco.com ↑

- www.greenfibres.com ↑

- With consideration the contamination at the reclaiming of fibres stage can be kept to a minimum ↑